Another book review. I'm posting these across my blogs, with blog-specific content at the end.

The Cult of LEGO, John Baichtal and Joe Meno, 2011, No Starch Press.

Okay, I'm embarrassed. I've had this one sitting here to review for just about a year now. I've been hesitant because I didn't want to be negative, but I suppose that's not a concern one should have in reviewing books. The thing is, from the point I first heard of this book, I wanted to love it. And, don't get me wrong, there is so much to love about this book. And before I go any further on a negative note, I want to start out celebrating what I love about this. We all know Joe as the founder and editor of

BrickJournal, and a look at his

Flickr stream reveals that he can be found at just about every gathering of more than five AFOLs, snapping picture after picture of all the great MOCs in the community. And the photos here are stunning - both those by Joe at fan events and photos chosen from builders across the community. This book tries to comprehensively cover all aspects of the hobby. The text by John Baichtal starts with a history of the company, then goes into all different areas, like different themes, spotlights on builders, NXT building, brick comics, LEGO in education, fan fests, micro macro sculpture and figs, Legoland parks, customization, Lugnet, and pretty much anything else you can think of.

There, I suppose is what bothered me. I love the photos. Yes, with anything like this you're going to quibble with 'why did they include this and not the five thousand other MOCs that they should have?' I suppose part of this comes down to taste, or luck, or maybe just which builders gave permission to use their photos. The text, though, tries to do too much, and it doing so it falls kind of flat. The style is more reporting, and lacks the personal feel we get in something like Jonathan Bender's

LEGO: A Love Story. Actually, this book works best as the illustrations that were missing from Bender's book. In addition to the lack of a real emotional connection, there are odd inclusions and exclusions. I completely understand how a favorite MOC can be overlooked, but there are some glaring omissions in the text. For instance, the Castle theme gets less than a page (with a few additional MOCs that show up elsewhere). This is much less coverage than some individual builders or MOCs. Now, I'm a castle guy, so maybe I'm being sensitive to my favorite area of building, but Castle is one of the 'big three' themes along with Town and Space. Also, the coverage of the online community is sorely lacking. If you read this, you'd think that the community consists primarily of Lugnet and the Brothers-Brick. Miniland building is another shortfall. Sure, there aren't a ton of people who build in this scale, but it's at the heart of the theme parks, and in the book miniland figures get about a third as much space as Homemaker and Belville figs. Some inclusions are odd. There seems to be a huge emphasis on FFOLs. I'm not complaining about including women builders prominently, but it seems a bit agenda driven - trying to prove that LEGO isn't just for boys. There are also some individuals who get featured again and again - no knock on them, but it just seems that there are so many who get overlooked that to put a lot of attention on a few seems misplaced. The book does cover some areas that are left out of other LEGO books I've seen, like First LEGO League and Serious Play. I guess part of the problem is that there is no narrative thread that runs through the book. It's more like a scatter-shot of short pieces that tries to cover everything, but is inevitably hit and miss.

I'm really sorry to be negative on this book, which is why I've put off reviewing it. I do think that as a peek into the community it works well, and as a coffee table book to pick up and flip through the pictures, but to sit down and read to get some comprehensive insight I think it falls short of the high mark it set for itself. Anyway, if you're into LEGO books, you probably already have this. If you don't, I might turn first to one of the other books on the market.

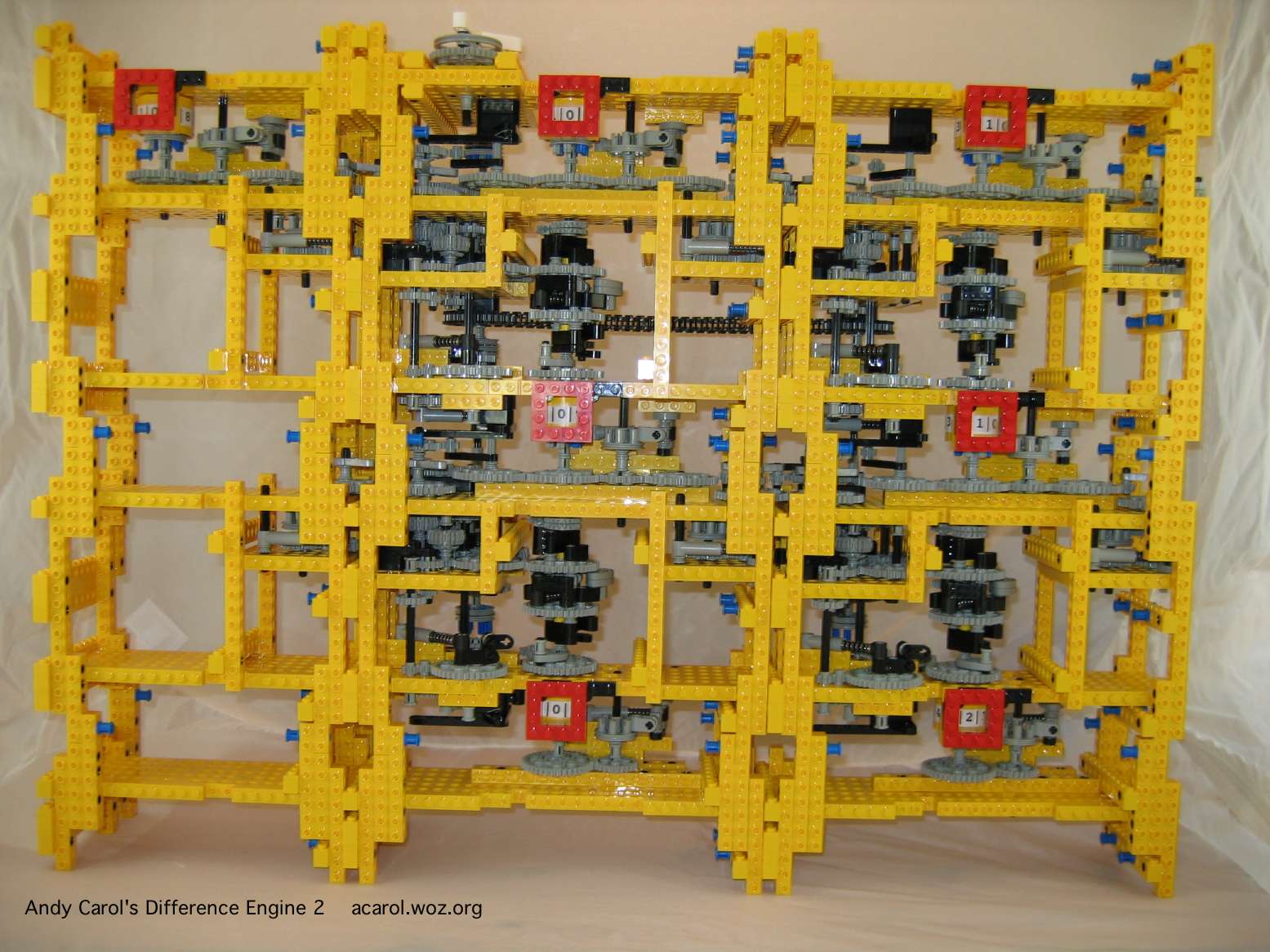

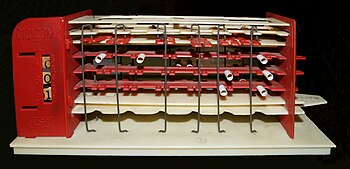

SciBricks specific content - Actually quite a bit. We see several great dinosaurs including Henry Lim's lifesize stegosaurus. There is a lot about robotics with Mindstorms NXT and the First LEGO League. There's a feature on high altitude experiments involving LEGO and weather balloons. Andrew Carol's working LEGO replicas of Babbage's Difference Engine and the Antikythera mechanism get a three page spread.