Friday, October 18, 2013

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla, shown here by Connor Wingard, was an engineer and prolific inventor. He is known, among other things, for his important work in competition with Edison, developing electricity as a practical source of energy for consumers, including the development of alternating current.

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Book review: Beautiful LEGO

Beautiful LEGO by Mike Doyle, 2013, No Starch Press

Please note that I'm posting this same review across my blogs, but I'm appending some blog-specific information at the end of each review.

A little while ago, Huw on Brickset noted the explosion of LEGO books in recent years. Some of those books are little more than catalogues of LEGO products (the 'here are all of the figures in the Harry Potter sets' type books), the really great thing about this trend is the great number of those books that are by, for, and about the AFOL community. The most recent addition to the growing bibliography is Mike Doyle's Beautiful LEGO, published by No Starch Press.

Beautiful LEGO is exactly what the title implies, a celebration of LEGO MOCs that are particularly gorgeous. The emphasis here is on the pictures - of the 266 pages in the book, only 17 of them have text. These text pages include a one page intro by Doyle about inspiring artistic MOCs and the creativity of the AFOL community, and a series of one to three page interviews with some of the builders. By my count 81 different builders contributed over 360 different MOCs. The subject matter is completely varied, from microscale buildings to full scale sculptures of everyday objects. The arrangement of MOCs is varied - in places Doyle gives several different builders' takes on the same subject matter, and in other places he places the spotlight on individuals, grouping a series of MOCs by the same person. The creations themselves run from humorous MOCs like some of Angus MacLane's Cube Dudes to some that are bright and fun like Thomas Poulsom's birds, to others that are dark and foreboding, like Doyle's own abandoned homes. As you can see from just those three examples, the builders include a lot of names that would be familiar to anyone who is active in the AFOL community - indeed most of the MOCs are ones I've seen featured on the various LEGO blogs. But just because I've seen them before, and by virtue of being someone reading my blogs you probably have as well, doesn't mean this isn't a wonderful book to own. It's a great collection of some of the best of the best, and perfect to peruse for inspiration, or just leave on your coffee table to amaze your non-LEGO friends. Indeed, I think this would be a great gift for a non-AFOL who just likes cool things (and it may even convert them into an AFOL).

Beautiful LEGO has one really nice thing that I think may be a unique innovation in this book. There is an index of contributors at the back, and for almost all of them Doyle provides a URL of where to find their work online (Flickr stream, personal site, a couple of MOCpages), and he includes the nickname they use on LEGO forums. This is great in a hobby where sometimes I only know people by their forum handles (indeed, since I've never been to a major AFOL convention, I still half believe that people look like their sig figures). I think this resource is a great tribute to the true heroes of the book, the community of awesome builders.

So are there any problems with this book? Sure. There's the unavoidable problem of selection. In the potentially infinite creativity of a worldwide community you'll always be able to ask "why not include this, or that?", a problem that Doyle recognizes in the preface. I'm a castle guy, and I would have loved to have seen more castles. I've been judging castle contests for a decade and could point to hundreds of castle MOCs that could easily sit alongside the other creations here. One critique that goes to No Starch rather than Doyle is that this really should be a hard cover book, in keeping with other coffee table books focused on beautiful pictures. A very minor critique is that two of the photos on the back cover are cut off at the top of the page. I think they were going for the effect of it looking like an endless collage of photos that keeps going, but if this were so they should have photos leading off all four sides of the page. My main critique, though, is with the presentation of the MOCs. Don't get me wrong, they are all high quality photos. Almost all of the photos are clear shots of the whole MOC in good lighting taken from the front, or with the MOC turned slightly to one side, with the camera looking slightly down. I guess in a book that was all about the creativity of the MOCs, I would have appreciated some more creativity of the photography - maybe some with different lighting effects, in silhouette, or with different filters on the camera, or some closeup details, or looking up at the moc from the base, that sort of thing.

On my blog ArtisticBricks I have several times asked the question "Is LEGO art?" or at least "Can LEGO be art?" Doyle answers that question with a resounding yes. One interesting thing I note is that while the minifig is ubiquitous in the world of AFOLs, there are almost no figs in this book. I wonder what that means? Is this just a reflection of Doyle's choices, or an indication that the fig is the distinction between playing and creating? That's something to think about, and I'd love to hear people's thoughts. Regardless, though, in this book Doyle has assembled a great portfolio of evidence that show that this thing we love is no mere toy, but a true medium for expression.

Blog-specific content: The science-themed MOCs in the book include Guy Himber's Orrery and Dave Kaleta's Frog Dissection. I keep meaning to feature Thomas Poulsom's birds, since they are so accurate they could illustrate an ornithology textbook.

Please note that I'm posting this same review across my blogs, but I'm appending some blog-specific information at the end of each review.

A little while ago, Huw on Brickset noted the explosion of LEGO books in recent years. Some of those books are little more than catalogues of LEGO products (the 'here are all of the figures in the Harry Potter sets' type books), the really great thing about this trend is the great number of those books that are by, for, and about the AFOL community. The most recent addition to the growing bibliography is Mike Doyle's Beautiful LEGO, published by No Starch Press.

Beautiful LEGO is exactly what the title implies, a celebration of LEGO MOCs that are particularly gorgeous. The emphasis here is on the pictures - of the 266 pages in the book, only 17 of them have text. These text pages include a one page intro by Doyle about inspiring artistic MOCs and the creativity of the AFOL community, and a series of one to three page interviews with some of the builders. By my count 81 different builders contributed over 360 different MOCs. The subject matter is completely varied, from microscale buildings to full scale sculptures of everyday objects. The arrangement of MOCs is varied - in places Doyle gives several different builders' takes on the same subject matter, and in other places he places the spotlight on individuals, grouping a series of MOCs by the same person. The creations themselves run from humorous MOCs like some of Angus MacLane's Cube Dudes to some that are bright and fun like Thomas Poulsom's birds, to others that are dark and foreboding, like Doyle's own abandoned homes. As you can see from just those three examples, the builders include a lot of names that would be familiar to anyone who is active in the AFOL community - indeed most of the MOCs are ones I've seen featured on the various LEGO blogs. But just because I've seen them before, and by virtue of being someone reading my blogs you probably have as well, doesn't mean this isn't a wonderful book to own. It's a great collection of some of the best of the best, and perfect to peruse for inspiration, or just leave on your coffee table to amaze your non-LEGO friends. Indeed, I think this would be a great gift for a non-AFOL who just likes cool things (and it may even convert them into an AFOL).

Beautiful LEGO has one really nice thing that I think may be a unique innovation in this book. There is an index of contributors at the back, and for almost all of them Doyle provides a URL of where to find their work online (Flickr stream, personal site, a couple of MOCpages), and he includes the nickname they use on LEGO forums. This is great in a hobby where sometimes I only know people by their forum handles (indeed, since I've never been to a major AFOL convention, I still half believe that people look like their sig figures). I think this resource is a great tribute to the true heroes of the book, the community of awesome builders.

So are there any problems with this book? Sure. There's the unavoidable problem of selection. In the potentially infinite creativity of a worldwide community you'll always be able to ask "why not include this, or that?", a problem that Doyle recognizes in the preface. I'm a castle guy, and I would have loved to have seen more castles. I've been judging castle contests for a decade and could point to hundreds of castle MOCs that could easily sit alongside the other creations here. One critique that goes to No Starch rather than Doyle is that this really should be a hard cover book, in keeping with other coffee table books focused on beautiful pictures. A very minor critique is that two of the photos on the back cover are cut off at the top of the page. I think they were going for the effect of it looking like an endless collage of photos that keeps going, but if this were so they should have photos leading off all four sides of the page. My main critique, though, is with the presentation of the MOCs. Don't get me wrong, they are all high quality photos. Almost all of the photos are clear shots of the whole MOC in good lighting taken from the front, or with the MOC turned slightly to one side, with the camera looking slightly down. I guess in a book that was all about the creativity of the MOCs, I would have appreciated some more creativity of the photography - maybe some with different lighting effects, in silhouette, or with different filters on the camera, or some closeup details, or looking up at the moc from the base, that sort of thing.

On my blog ArtisticBricks I have several times asked the question "Is LEGO art?" or at least "Can LEGO be art?" Doyle answers that question with a resounding yes. One interesting thing I note is that while the minifig is ubiquitous in the world of AFOLs, there are almost no figs in this book. I wonder what that means? Is this just a reflection of Doyle's choices, or an indication that the fig is the distinction between playing and creating? That's something to think about, and I'd love to hear people's thoughts. Regardless, though, in this book Doyle has assembled a great portfolio of evidence that show that this thing we love is no mere toy, but a true medium for expression.

Blog-specific content: The science-themed MOCs in the book include Guy Himber's Orrery and Dave Kaleta's Frog Dissection. I keep meaning to feature Thomas Poulsom's birds, since they are so accurate they could illustrate an ornithology textbook.

Wednesday, October 9, 2013

Chemistry prize!

Congratulations to Karplus, Levitt and Warshel on the 2013 Chemistry Nobel. These three made important strides in integrating the two sides of computational modeling. Computational chemists use two different methods to simulate molecules and make predictions about their structures and properties. Molecular mechanics, MM, uses classical physics and treats atoms as balls and springs. This does not give very exact answers, but these calculations are very fast and can be used for large systems (e.g. proteins). Quantum mechanics, QM, treats electrons individually. This gives very exact answers, but molecules that have only ten or twenty atoms can sometimes take many hours to complete, so things like proteins would take lifetimes to calculate. QM/MM is the solution. Karplus, Levitt and Warshel worked out ways to integrate the two methods so that large systems could be broken into parts, with part treated with MM and the other part treated with QM. This allows you to take some big system, like an enzyme, and very quickly solve the structure of the larger part with MM, but closely model reactions in the active site using QM.

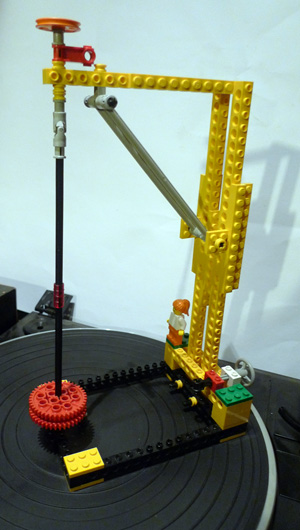

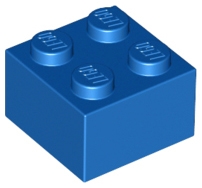

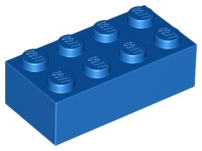

To make an analogy, let's look at DUPLO and System LEGO. DUPLO are the larger blocks built for young children (my almost-2-year-old loves to chew on these). System bricks are what you probably think of as LEGO. You may not have realized it, but these two types of pieces can be combined:

Some LEGO builders use this trick when making large creations. DUPLO bricks are larger, and can quickly build up big mountains or whatever, but System bricks can be used to make the final result much more detailed. Here we see this principle in a WIP of a train display.

Now, this isn't so hard, since DUPLO and System bricks are both by LEGO, and they designed these to integrate. But QM/MM is a different matter. The theories underlying them are completely unrelated, and the real difficulty that faced Karplus, Levitt and Warshel (and others) and the reason they were recognized by the Nobel committee, was how to develop tools that connected them together in a meaningful way. A couple of years ago, Golan Levin and Shawn Sims came up with a series of connection pieces that can link LEGO, Lincoln Logs, TinkerToys, and other building toys. They don't sell them, but they made the designs available so you can make your own with a 3D printer.

With these you can link up previously-unconnected constructions. It's QM/MM for the building toy world! Hmm, is their a Nobel for toys?

To make an analogy, let's look at DUPLO and System LEGO. DUPLO are the larger blocks built for young children (my almost-2-year-old loves to chew on these). System bricks are what you probably think of as LEGO. You may not have realized it, but these two types of pieces can be combined:

Some LEGO builders use this trick when making large creations. DUPLO bricks are larger, and can quickly build up big mountains or whatever, but System bricks can be used to make the final result much more detailed. Here we see this principle in a WIP of a train display.

Now, this isn't so hard, since DUPLO and System bricks are both by LEGO, and they designed these to integrate. But QM/MM is a different matter. The theories underlying them are completely unrelated, and the real difficulty that faced Karplus, Levitt and Warshel (and others) and the reason they were recognized by the Nobel committee, was how to develop tools that connected them together in a meaningful way. A couple of years ago, Golan Levin and Shawn Sims came up with a series of connection pieces that can link LEGO, Lincoln Logs, TinkerToys, and other building toys. They don't sell them, but they made the designs available so you can make your own with a 3D printer.

With these you can link up previously-unconnected constructions. It's QM/MM for the building toy world! Hmm, is their a Nobel for toys?

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Physics prize!

Alright, after leaving a few hours for the medicine and physiology to have the top position here, it's time to celebrate the 2013 Physics Nobel, awarded to François Englert and Peter W. Higgs, for their work on the Higgs boson going back fifty years. They developed a theory that unified the weak interaction and electromagnetism and helps explain the Standard Theory of matter. One prediction of their theory was the Higgs boson, which was first observed experimentally about a year ago and confirmed earlier this year. These experiments were performed at CERN, in part using the ATLAS detector, here in LEGO form by Dr. Sascha Hehlhase.

So, anyone want to take bets on the Chemistry prize? I'll be following #nobel on Twitter early tomorrow morning to get the announcement because, yes, I'm that big a geek.

So, anyone want to take bets on the Chemistry prize? I'll be following #nobel on Twitter early tomorrow morning to get the announcement because, yes, I'm that big a geek.

Nobel week!

Okay, in my general blogging malaise recently, I've gotten behind in the most exciting week for science geeks. Better than March Madness, better even than Shark Week, it's Nobel week! Monday (okay, it was a day ago, I missed it), is Physiology or Medicine Day. The 2013 prize was jointly awarded to James E. Rothman, Randy W. Schekman and Thomas C. Südhof. These three scientists have done groundbreaking work in examining how molecules are moved around in the cell. Molecules are wrapped up in membrane bound parcels called vesicles. These three looked at how the transfer of these parcels and their unwrapping to release their contents is regulated in the cell. Essentially they worked out how the cellular post office works (this picture is of an official DUPLO set, btw).

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

Scientist

Most days I look at recent headlines for 'LEGO' on Google news, and about a week ago there was a real spate of articles on the scientist fig that came out in series 11 of the Collectible Minifig line. First up, I just want to note that I really like this fig; I got three of them so I can mix and match to help populate laboratory scenes. The lab coat is nice, the blue hands are just the right shade to be the same nitrile gloves I wear all the time in lab, and it's a great source of two erlenmeyer flasks.

But the series of articles really bugged me. The meme that runs through all of these is that "at last, LEGO gives us a woman scientist", or "Lego breaks the plastic ceiling", etc. I really think this started as a post somewhere (Huffington) and then got picked up by bloggers at a bunch of different news sites. The idea seems to be that LEGO has been keeping women down all these years, and now they can finally become scientists. Okay, let's look more closely. First, this just isn't true. If you do a quick search you can find out that there have been a handful of minifigs called "scientist" before, and three of them were women. Okay, these all came in a First LEGO League set (which was perfectly gender-balanced, btw), and they weren't detailed figs, so maybe we should discount them.

Also in the meme-busting department, we seem to have quickly forgotten the Friends set Olivia's Invention Workshop, where Olivia seems to simultaneously be performing chemistry experiments, inventing robots, and solving mathematical equations (and, while I do not know of every LEGO set, I cannot find any official set that has a boy doing these things). But, of course, to acknowledge sets like that would go against another very popular meme that the Friends line is this horribly oppressive series of sets that forces girls to giggle in hair salons and cupcake bakeries rather than, say, climb trees, learn karate, fly planes, skateboard, work on computers, camp, and drive sports cars, speedboats and jetskis. But what are facts in the face of a good meme?

Okay, let's go on to the nature of LEGO itself. Don't these editorial writers realize that LEGO figs are completely interchangeable? My son figured out at three that you can make whatever fig you want by switching the heads and hats etc around. So if you wanted to make a fig a woman, that would take about two seconds. But, of course, that begs the question, what makes a woman in LEGO fig world? Basically two things - overdone lipstick (and a lack of beards) for the faces and/or long hair. Leaving aside that men can have long hair and women short hair, and that not everyone wears excessive makeup in the workplace, for the first ten years of minifigs all figs had the same generic smiley face, and if figs are wearing hats, there is no hair piece. So tons of figs have no gender whatsoever. You can decide to call this one a man and that one a woman based on your complete whim.

I intentionally selected that fig because she, or he, is a doctor, and I wanted to point out that the very first doctor fig back in 1978 was ... drumroll please ... a woman (at least in that she had 'girl hair').

Indeed, the two doctor figs in 1980 were women, in 1981 there were two women and two non-gendered doctors (i.e. generic faces and hats), in 1982 another woman, and finally in 1985 we broke the plastic ceiling and a man could become a doctor! (Or maybe this was just a woman with short hair?) So in medicine, it seems that the high heel is on the other foot. Of course, those are doctors, and doctors aren't scientists, right? (My sister-in-law the neurologist would certainly dispute that). Let's get back to our proscribed story line and talk about how LEGO has been keeping women down by having men be all of the scientists (leaving aside, of course, the scientists from the aforementioned First LEGO League set and anyone in the medical sciences) (oh, Dan below mentioned marine biologists in the Divers line, so this is just the list of those with official names including the word 'scientist'). Here they are:

Okay, these can be grouped into three categories. The first three on the list above come from various space sets, in which they often had as colleagues women who were astronauts (again, most astronauts are also pretty serious scientists). The next group aren't really scientists, they're mad scientists. I've known some fairly odd people in my role as a chemist, but none of them was building a monster out of spare body parts dug up by their hunchbacked sidekick. I don't really think we can count these guys. Finally we have poor Ron Perkins, who has a brief role in the 2002 Spider-Man movie, only to be murdered by Willem Dafoe's Green Goblin. I really wouldn't call most of these guys 'scientists' in the sense that we see them doing science (I guess I'd leave out a couple of the guys from the space sets). I'd love to see sets where LEGO showed scientists at work looking through telescopes and microscopes, mixing chemicals and the like. A little while ago there was a big push by some agenda-driven posters to get the Female Scientist Minifigure Cuusoo proposal over the 10,000 mark. But what many (most?) of the proponents failed to see was that that set idea was not cool because it showed women scientists at work, but because it showed scientists at work, and I think that really tipped their hands that they're not really interested in science at all, but rather in their view of gender politics.

So, back to my new favorite fig. I love you, but don't pay attention to all of those news bloggers and pseudo-social-scientists who think the important thing about you is that second X chromosome. I could give a rip about your gender. What gets me excited is that you're a freakin' scientist! (And, just to fly my own flag, you're a chemist to boot.)You go, girl! You go, scientist!

But the series of articles really bugged me. The meme that runs through all of these is that "at last, LEGO gives us a woman scientist", or "Lego breaks the plastic ceiling", etc. I really think this started as a post somewhere (Huffington) and then got picked up by bloggers at a bunch of different news sites. The idea seems to be that LEGO has been keeping women down all these years, and now they can finally become scientists. Okay, let's look more closely. First, this just isn't true. If you do a quick search you can find out that there have been a handful of minifigs called "scientist" before, and three of them were women. Okay, these all came in a First LEGO League set (which was perfectly gender-balanced, btw), and they weren't detailed figs, so maybe we should discount them.

Also in the meme-busting department, we seem to have quickly forgotten the Friends set Olivia's Invention Workshop, where Olivia seems to simultaneously be performing chemistry experiments, inventing robots, and solving mathematical equations (and, while I do not know of every LEGO set, I cannot find any official set that has a boy doing these things). But, of course, to acknowledge sets like that would go against another very popular meme that the Friends line is this horribly oppressive series of sets that forces girls to giggle in hair salons and cupcake bakeries rather than, say, climb trees, learn karate, fly planes, skateboard, work on computers, camp, and drive sports cars, speedboats and jetskis. But what are facts in the face of a good meme?

Okay, let's go on to the nature of LEGO itself. Don't these editorial writers realize that LEGO figs are completely interchangeable? My son figured out at three that you can make whatever fig you want by switching the heads and hats etc around. So if you wanted to make a fig a woman, that would take about two seconds. But, of course, that begs the question, what makes a woman in LEGO fig world? Basically two things - overdone lipstick (and a lack of beards) for the faces and/or long hair. Leaving aside that men can have long hair and women short hair, and that not everyone wears excessive makeup in the workplace, for the first ten years of minifigs all figs had the same generic smiley face, and if figs are wearing hats, there is no hair piece. So tons of figs have no gender whatsoever. You can decide to call this one a man and that one a woman based on your complete whim.

I intentionally selected that fig because she, or he, is a doctor, and I wanted to point out that the very first doctor fig back in 1978 was ... drumroll please ... a woman (at least in that she had 'girl hair').

Indeed, the two doctor figs in 1980 were women, in 1981 there were two women and two non-gendered doctors (i.e. generic faces and hats), in 1982 another woman, and finally in 1985 we broke the plastic ceiling and a man could become a doctor! (Or maybe this was just a woman with short hair?) So in medicine, it seems that the high heel is on the other foot. Of course, those are doctors, and doctors aren't scientists, right? (My sister-in-law the neurologist would certainly dispute that). Let's get back to our proscribed story line and talk about how LEGO has been keeping women down by having men be all of the scientists (leaving aside, of course, the scientists from the aforementioned First LEGO League set and anyone in the medical sciences) (oh, Dan below mentioned marine biologists in the Divers line, so this is just the list of those with official names including the word 'scientist'). Here they are:

Okay, these can be grouped into three categories. The first three on the list above come from various space sets, in which they often had as colleagues women who were astronauts (again, most astronauts are also pretty serious scientists). The next group aren't really scientists, they're mad scientists. I've known some fairly odd people in my role as a chemist, but none of them was building a monster out of spare body parts dug up by their hunchbacked sidekick. I don't really think we can count these guys. Finally we have poor Ron Perkins, who has a brief role in the 2002 Spider-Man movie, only to be murdered by Willem Dafoe's Green Goblin. I really wouldn't call most of these guys 'scientists' in the sense that we see them doing science (I guess I'd leave out a couple of the guys from the space sets). I'd love to see sets where LEGO showed scientists at work looking through telescopes and microscopes, mixing chemicals and the like. A little while ago there was a big push by some agenda-driven posters to get the Female Scientist Minifigure Cuusoo proposal over the 10,000 mark. But what many (most?) of the proponents failed to see was that that set idea was not cool because it showed women scientists at work, but because it showed scientists at work, and I think that really tipped their hands that they're not really interested in science at all, but rather in their view of gender politics.

So, back to my new favorite fig. I love you, but don't pay attention to all of those news bloggers and pseudo-social-scientists who think the important thing about you is that second X chromosome. I could give a rip about your gender. What gets me excited is that you're a freakin' scientist! (And, just to fly my own flag, you're a chemist to boot.)

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Foucault's Pendulum

Today's Google doodle celebrates the 194th anniversary of Léon Foucault's birth. Foucault was a French physicist who did work on such areas as magnetism and momentum, but his two most notable accomplishments were an early measure of the speed of light, and his pendulum demonstrating the rotation of the Earth. Imagine a pendulum hanging over a turntable. If you start the pendulum swinging, it will go back and forth in a straight line. If you start the turntable spinning, an ant on the turntable would see the pendulum doing loops from his perspective. If you attached traced out the route of the swinging pendulum on the spinning turntable, you'd get a design something like the Spirograph art I remember from when I was a kid. Foucalt found that with freely swinging pendulum with a long enough arm, you could actually see the effect of the spinning planet. This effect is strongest at the north and south pole, and disappears at the equator - so you can use the magnitude of the effect to determine your latitude.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Happy birthday, Classic-Castle!

In addition to maintaining my little family of LEGO blogs, I'm also actively involved in Classic-Castle.com, the source for all your LEGO Castle needs. Classic-Castle just turned ten years old! In recognition of that, let's feature something appropriately themed. Here is

Vitruvian Man, as drawn by Kevin Hinkle. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, was an artist, inventor, mathematician, philosopher and scientist. He took over 13,000 pages of notes, describing his inventions, his observations of nature and anatomy, and writings on natural philosophy. The Vitruvian Man is his study on the proportions of the human body, in connection to geometry.

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

ESCHER space station

Sorry about the lack of blog posts for three weeks, life has been hectic. In the meantime I've bookmarked a lot of MOCs to put here. For instance, David Roberts built the ESCHER space station, based on the Penrose triangle.

Monday, August 12, 2013

Schrödinger's cat

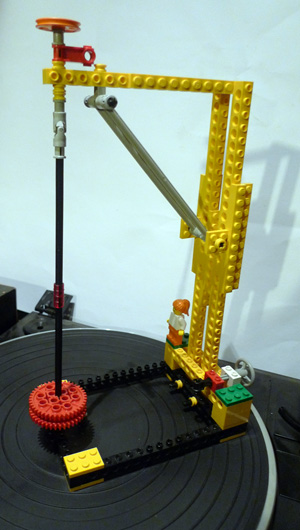

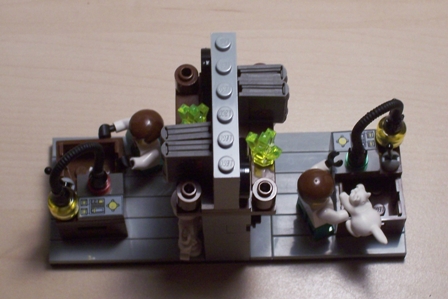

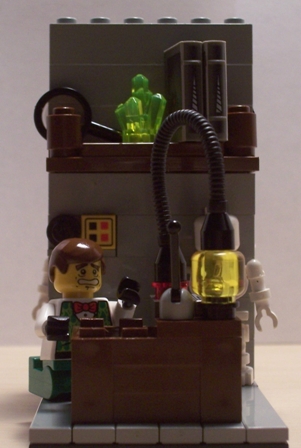

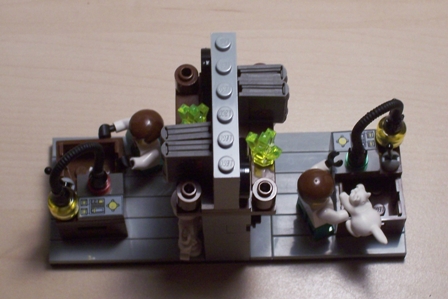

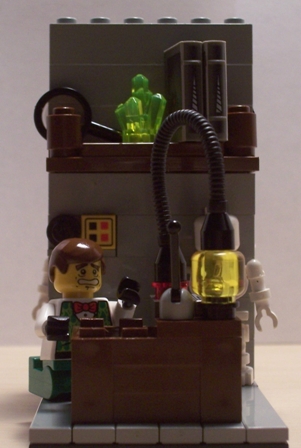

Today's Google doodle remembers Erwin Schrödinger, one of the key figures in the development of quantum mechanics and winner of the 1933 physics Nobel. In my day job I'm a computational chemist, and my work largely depends on using computer models that approximate Schrödinger's equation that is used to describe the arrangement of electrons in molecules. In the popular eye he is remembered for his "Schrödinger's cat" thought experiment. He was critical of a particular interpretation of quantum mechanics that says that for certain phenomena that could equally exist in two different states, say, for instance, the spin of an electron, the resolution of the two states is dependent on an observer - that is, until someone measures it, the electron equally exists in both states. In his argument, he asked us to imagine a cat in a box. Somehow, the release of a poison is rigged to the decay of a radioactive atom. Since it is impossible to predict whether the atom will decay or not until it is observed, under the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, the cat is both dead and alive until you open the box. I think most people actually misinterpret his point. He wasn't actually saying the cat is both dead and alive simultaneously, instead it was a reductio ad absurdum argument, showing how the Copenhagen interpretation can to obviously ridiculous conclusions.

For our LEGO illustration, here is a two-sided scene by Sea Serpent. On one side the scientist (Schrödinger, presumably) opens the box to hug his cat, on the other side he is distressed to find his cat is dead.

For our LEGO illustration, here is a two-sided scene by Sea Serpent. On one side the scientist (Schrödinger, presumably) opens the box to hug his cat, on the other side he is distressed to find his cat is dead.

Saturday, August 10, 2013

Trieste

FifthPixel made this great rendition of the bathyscaphe Trieste. On January 23, 1960, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh reached the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, the deepest part of the ocean at 10,911 meters. This feat was not repeated until last year (by Titanic director James Cameron).

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

Jill Tarter & Jocelyn Bell Burnell

I've previously blogged cookies of LEGO Rosalind Franklin and Hedy Lamarr made by Wendy Staples of the Quirky Cookie for a ScienceGrrl event. I really need to feature her versions of Jill Tarter & Jocelyn Bell Burnell as well.

Tarter is an American radio astronomer, who has spent much of her career on the search for extra terrestrial intelligence (SETI), and she did other important work on astronomical bodies such as brown dwarfs. Carl Sagan based the character Ellie Arroway in his novel Contact in part on Tarter. BTW, you should really read that book. The book (NOT the movie) is full of great insights into life as a graduate student, the conduct of international science, thoughts about how information can be transmitted, descriptions of radio telescopes, and even a very thoughtful examination of the interaction of science and faith.

Bell Burnell is another important radio astronomer, from Northern Ireland. She has had a long career in science and academics, but is perhaps best known for her discovery of pulsars as a graduate student. There was a bit of a controversy in that her research adviser, Antony Hewish, was awarded half of the 1974 Nobel, and not Bell Burnell. The question of who gets the true credit for a discovery - student or teacher - has always been a question. For the record, Bell Burnell has said publicly that she did not have problems with the decision as it was in keeping with common practice, and she has received a lot of recognition and awards for her work.

Just for good measure, Wendy also made a bunch of generic scientists as well.

Tarter is an American radio astronomer, who has spent much of her career on the search for extra terrestrial intelligence (SETI), and she did other important work on astronomical bodies such as brown dwarfs. Carl Sagan based the character Ellie Arroway in his novel Contact in part on Tarter. BTW, you should really read that book. The book (NOT the movie) is full of great insights into life as a graduate student, the conduct of international science, thoughts about how information can be transmitted, descriptions of radio telescopes, and even a very thoughtful examination of the interaction of science and faith.

Bell Burnell is another important radio astronomer, from Northern Ireland. She has had a long career in science and academics, but is perhaps best known for her discovery of pulsars as a graduate student. There was a bit of a controversy in that her research adviser, Antony Hewish, was awarded half of the 1974 Nobel, and not Bell Burnell. The question of who gets the true credit for a discovery - student or teacher - has always been a question. For the record, Bell Burnell has said publicly that she did not have problems with the decision as it was in keeping with common practice, and she has received a lot of recognition and awards for her work.

Just for good measure, Wendy also made a bunch of generic scientists as well.

Monday, July 29, 2013

Atlas Detector

I've previously noted Dr. Sascha Hehlhase's LEGO rendition of the Atlas detector, used in the search for the Higgs boson. He's gone on and made a Cuusoo project of the Atlas detector, which subsequently received 10,000 votes. I seriously doubt this will become an official LEGO set, but it would be cool if kids all over were asking their parents to buy them a LEGO Atlas detector.

Saturday, July 27, 2013

Rotational symmetry

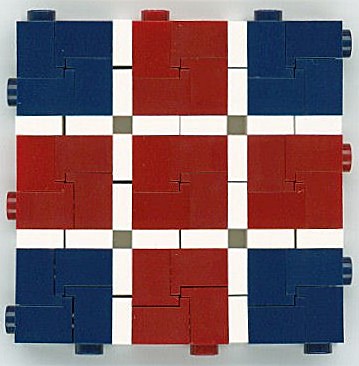

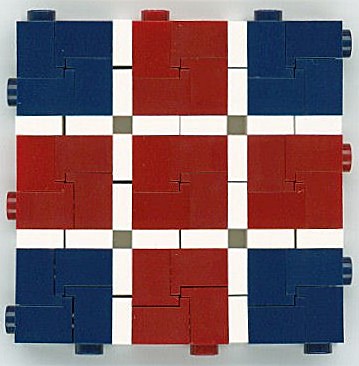

School kids at Dryden Elementary had a great lesson on rotational symmetry, creating mosaics with C4 axes. Via MosaicBricks.

Friday, July 26, 2013

Symmetry - Axis of Proper Rotation

Okay, back to symmetry, an axis of proper rotation (often just called a rotation axis, or a Cn axis) is a symmetry element found when you rotate an object by some fraction of 360 degrees and the result looks identical. E.g. if you rotated an equilateral triangle by 120 degrees, you would see the exact same triangle. This is called a C3 axis, since you are rotating by 1/3 of 360. Since LEGO bricks are mostly squares and rectangles and fit together most easily with 90 degree angles, it is pretty common to see LEGO creations with C4 or C2 axes (of course these often require that you ignore the word LEGO written on the studs or other minor imperfections that break symmetry).

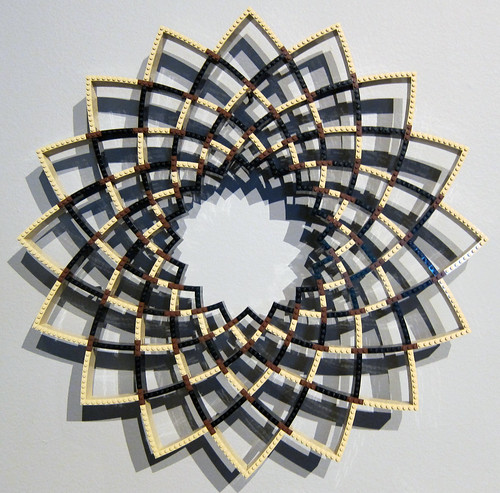

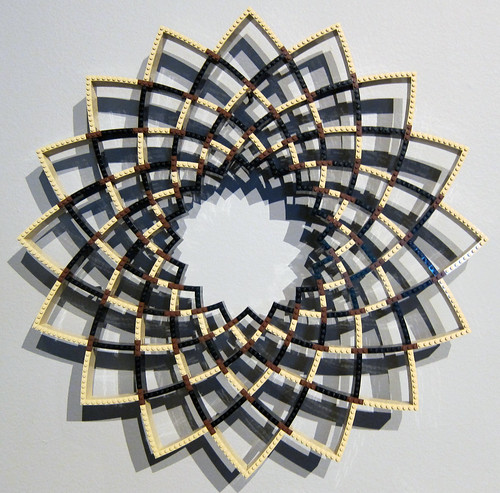

However, with some clever building, you can come up with LEGO creations with other rotational axes. These creations have C3, C5, C12 and C16 axes, respectively.

However, with some clever building, you can come up with LEGO creations with other rotational axes. These creations have C3, C5, C12 and C16 axes, respectively.

Thursday, July 25, 2013

Rosalind Franklin

I'll get back to symmetry tomorrow, but I'll do an aside today, spurred by the Google doodle in honor of what would have been Rosalind Franklin's 93rd birthday. I've peviously noted how important she was in the discovery of the structure of DNA. If she had not sadly passed away at a very young age, she surely should have been considered as part of the 1968 Nobel Prize. Last year Wendy Staples of the Quirky Cookie made a lot of science and women-scientist themed cookies for the launch party of the ScienceGrrl Calendar at the London Science Museum. ScienceGrrl is a British organization to promote science education, particularly to young girls. Anyway, here we see cookies of LEGO versions of Rosalind Franklin and Hedy Lamarr (best known for her movie career, but she also developed a radio frequency hopping technique that formed the basis for much of today's wireless technology). BTW, you really should go see all of the cookies. They're really cool, and I'm sure were perfect for a science themed event.

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Symmetry - mirror plane

Symmetry is a very important concept that is useful in all of the sciences. There are four basic symmetry elements - axis of proper rotation, axis of improper rotation, mirror plane, and point of inversion (technically these last two are only special cases of improper rotation, so you could correctly say there are only two symmetry elements). The most readily understood element is the mirror plane, where you can cut an object in half, and every point on one side of the mirror plane reflect across to an identical point on the other side. You're surrounded by objects with bilateral symmetry - a coffee cup, for instance, or the chair you're sitting on. Even the human body has rough bilateral symmetry if you ignore details like parting your hair to one side or wearing a watch on one arm and not the other. Here are a couple of LEGO objects with mirror planes, Pete Reid's LL-497 (if you ignore the Classic-Space logo) and Luis Baixinho's Butterfly.*

*Just to be pedantic, and before someone calls me on it, the fact that the word LEGO is written on the studs means than no LEGO object actually has bilateral symmetry, because you would have to have the mirror image word written on the other side of the creation.

*Just to be pedantic, and before someone calls me on it, the fact that the word LEGO is written on the studs means than no LEGO object actually has bilateral symmetry, because you would have to have the mirror image word written on the other side of the creation.

Monday, July 22, 2013

Friday, July 19, 2013

Working microscope

Carl Merrian built this Working microscope. It uses official LEGO elements like the magnifying glass element, technic gears, and fiber optic system to actually allow you to focus in on small objects.

Thursday, July 18, 2013

Jupiter control room

During my focus on illusions for the past couple of weeks, I've passed up some great creations, like Legodrome's Jupiter control room, which he created as a commission for the French space agency CNES.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)